This is the first article in a multi-part series to explore and understand the research done in developing language models to help debunk false information available in the public domain. There are many aspects of this system and I have separated them into multiple parts, each highlighting a particular research work that inspired me.

The autheticity of information has been a longstanding problem in the news industry, and the society at large. Coupled with social media platforms acting as a catalyst for information spread, false, distorted and inaccurate information has a tremendous potential in causing wide spread casualties to millions of users in a matter of minutes. They have been used as an effective tool in smearing political campaigns, undermining the effectiveness of proven scientific pratices such as vaccination and causing widespead hysteria in the general public. What makes matters worse is studies have shown that consumption of such fake news makes it harder for most people to accept, or even consider the truth.

Social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Google have come under severe backlash from a number of critics on their inability to effectively counter the fake news epidemic, as they should! Since at the heart of their service lies an algorithm that personalises content based on the user itself. Almost all social media platforms are tuned to offer personalized search-based results that essentially create a filter bubble - an echo chamber that serves the reader with content biased towards their own opinions. This gives the platform a dynamic in which the readers only encounter information that confirm their pre-existing beliefs.

To tackle this, a system needs to be put in place that can confirm the authenticity of any piece of information, almost instantly. Clearly a human based approach is neither feasible or scalable given the sheer enormity of the available data online. A machine learning model makes it easier to detect patterns from previously flagged articles, and therefore detect new ones. The first step is to create a dataset of claims, which would help train the model. Lets take the example of FEVER, one such dataset and delve into how it was created.

Note that the following article is my interpretation of the original work done by the authors and creators of FEVER. I have selected a subset of the white paper to help highlight the dataset creation process in this specific domain.

Creating a Fact Verification Dataset

One of the most famous datasets for factual verification is the FEVER - Fact Extract and VERification dataset. At its first release, the dataset consisted of 185,445 factual assertions (which has grown since) that are either true or false. They corelate to Wikipedia excerpts that either substantiate or refute them. The claims are classified under one of three categories - SUPPORTED, REFUTED and NOTENOUGHINFO. For the first two categories, the claims are accompanied with the correct evidence.

But how was this dataset created? This can be divided into two steps:

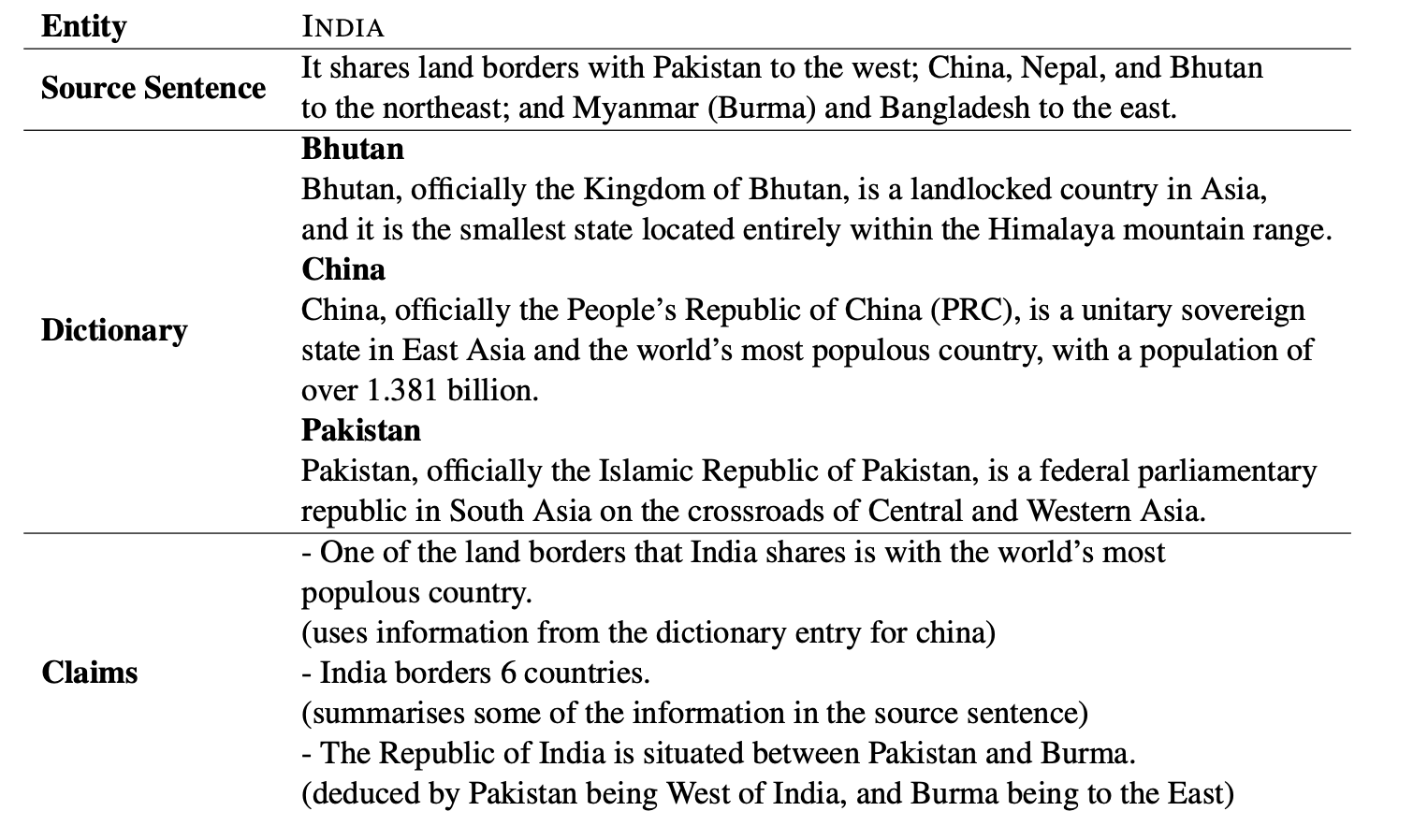

Claims Generation - To generate claims, information was first extracted from a Wikipedia dump (2017), processed along with the Stanford CoreNLP library and then sampled against 5,000 Wikipedia’s ‘most popular pages’ list and the hyperlinks contained in them. This information was then provided to annotators to generate a set of claims, focused on a single piece of information of the entity the Wikipedia page is about. The claims generated by them could range in the level of complexity depending on how they leverage the original information. In one case, they could simple paraphrase or simplify the original information creating a trivially verifiable claim. In the opposite case, they could incorporate their free-world knowledge on the topic and make the claim harder to verify through Wikipedia.

To tackle this, the creators introduced ‘dictionary’. The dictionary is a list of hyperlinked terms (contained in the original information) along with the first few lines of their corresponding pages. Annotators would use the dictionary to generate claims hence limiting the complexity.

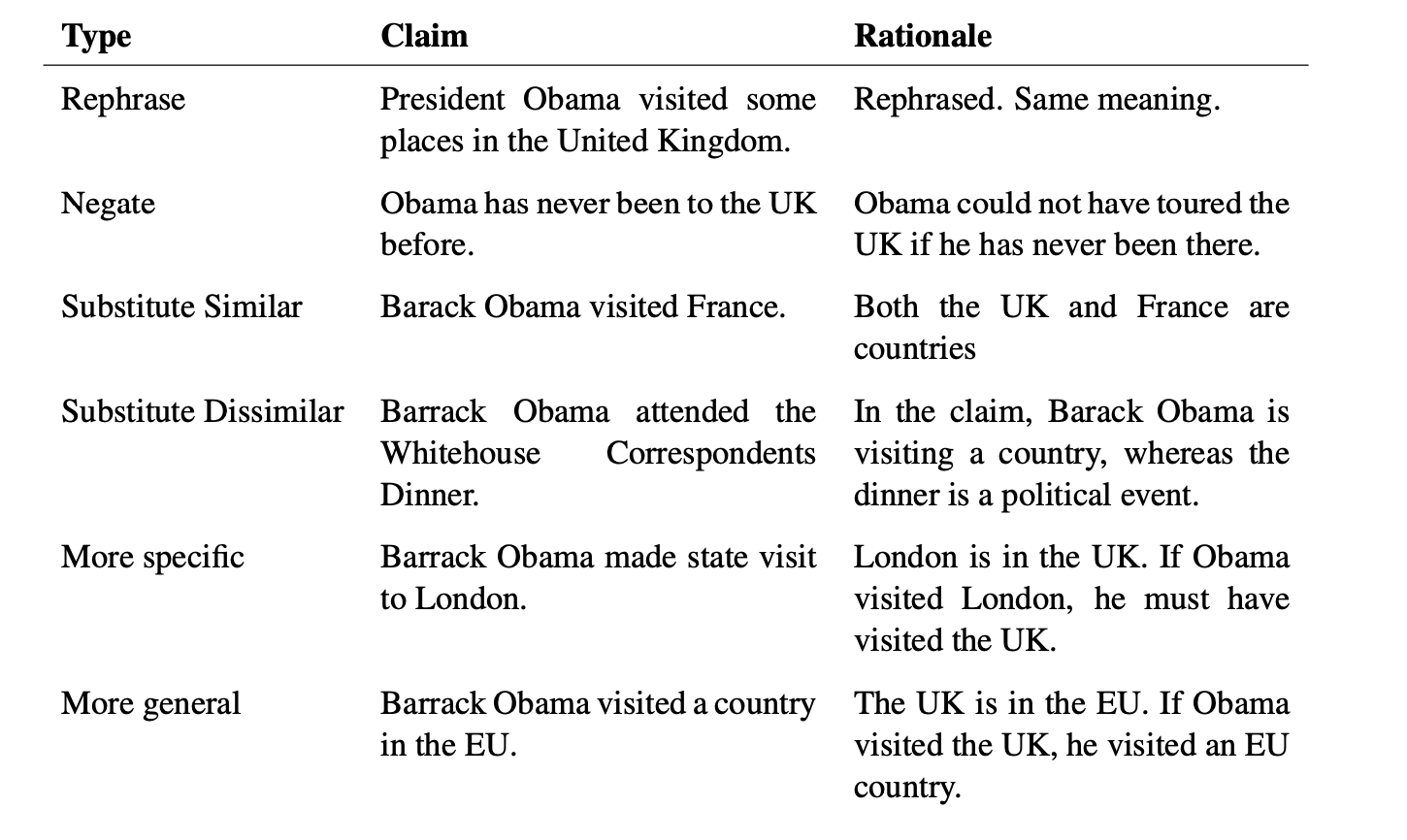

The annotators were also asked to mutate the claims by altering the original information under one of six different styles - paraphrasing, negation, substitution of an entity/relation with a similar/dissimilar one, and making the claim more general/specific.

One of the challenges the creators faced was the inability of the authors to create non-trivial negation mutations (negation mutations beyond adding ‘not’ to the original sentence). Apart from the examples provided for each type of mutation, the creators also highlighted the trivial negations (like ‘not’) to discourage it. This whole process resulted in an average token count per claim of 9.4 tokens, including both extracted and mutated claims.

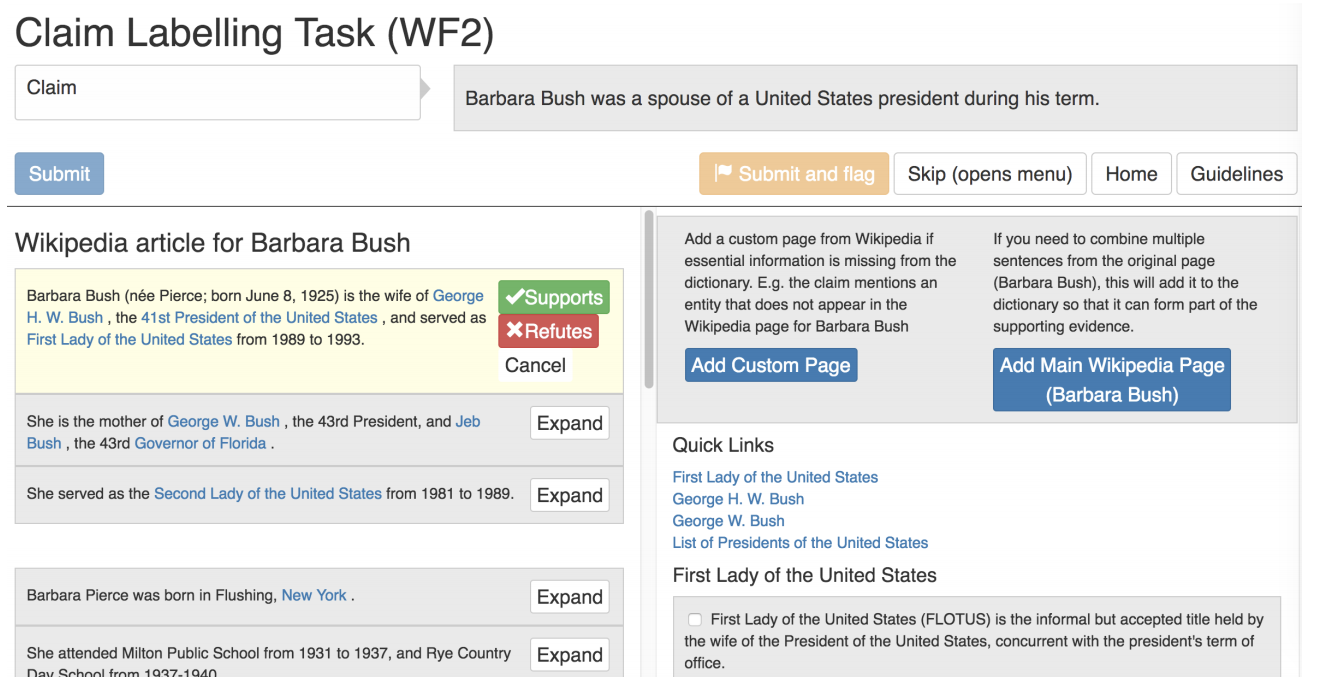

Claims Labeling - For each claim, the annotators were asked to label them as SUPPORTED, REFUTED or NOTENOUGHINFO. Through an interface, they had to provide evidence for the claims labelled in the first two categories. To help them in this process, they had been provided with the first few lines of the main entity in the claim’s page and the links in the dictionary. This was the supporting tool to help the annotators support or refute their claim. They also had the option of refering an external link, which would then be added to the list of available evidence for them to select from. If no amount of information could be found for a claim (either becuase it was too specific or too general), then the claim was marked NOTENOUGHINFO. Annotators were asked to not spend more than 2-3 minutes per claim.

Dataset Validation

Now that the claims dataset was ready with their respective tags and evidence, this dataset has to now be validated. The claim generation validation was done during the labelling process and as a result 1.01% of the claims were skipped, 2.11% contained typos and 6.63% of the generated claims were flagged as too vague/ambigious. The data validation was then done in three different ways:

- 5 - Way Agreement - From the dataset, 5% of the claims which were not skipped to be annotized were selected and a Fleiss’ κ score of 0.6841 was determined. Fleiss’ κ is used to measure the level of agreement between the raters or observers (in this case annotators) to see if they have similar results for a given claim. Higher the score, more the agreement.

- Agreement against Super-Annotators - Claims were randomly selected and 1% of them were given to Super-Annotators who had no time restriction and could search over the whole of Wikipedia to find sentences that could be used as evidence. The purpose of this was to provide as much coverage of the evidence as possible. This method resulted in a score of 95.42% and 72.36% respectively.

- Validation by Authors - The authors sampled 227 claims and found that 91.2% were accurately labelled with their claim and the supporting/refuting evidence. 3% of the claims were mistakes in claim generation that had not been flagged during labeling.

The authors also noted that of the most of the examples were incorrectly annotated were cases were the labels were correct but the eveidence selected was not sufficient. For example, the claim ‘Shakira is Canadian’ could be initially classified as REFUTED as the evidence ““Shakira is a Colombian singer, songwriter, dancer, and record producer” can support it. But there is a possibility where more explicit evidence such as “She was denied Canadian citizenship” could give. In that case, the authors argue that unless more information is provided and the annotators world knowledge is not factored in, the claim should be marked as NOTENOUGHINFO.

Hopefully the example of the FEVER dataset gives you a good idea on how a dataset can be constructed to help classify claims based on evidence (if any).